Dear Colleague:

Dear Colleague:

On May 13, the NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute hosted the first national TB Expert Network Conference via web-based seminar. Held bimonthly by the RTMCCs on a rotation basis, these conferences will provide a forum for expert medical consultants to discuss complicated treatment and case management issues and to foster education and capacity building among TB program consultants. TB medical consultants in TB programs in the Northeastern RTMCC are always invited to attend and will be able to view archived conferences.

We are pleased to report in this issue our first effort of taking the popular TB Intensive Workshop on the road to Toledo, Ohio. The course’s success was due in large part to the collaborative planning activities among our colleagues from the four TB programs that sent participants: Detroit, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio.

We are also excited about launching a series of articles

on the practical contribution of behavioral and social

sciences to the control and prevention of TB. On the

medical consultation front, we present the 2007 results of

the consultation requests from TB program staff and other

health care providers in the Northeastern Region. Finally,

this issue features a profile of Nancy Baruch, RN, MBA, TB Controller for Maryland, who is regionally and nationally recognized as a leader

in TB control efforts.

And, as usual, if you have any feedback for any of us, on any TB related topic, I

invite you to contact me or a member of our RTMCC staff at (973-972-3270).

Lee B. Reichman, MD, MPH

Executive Director

Northeastern RTMCC and the

Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

TB Intensive Workshop – On the Road

For the first time, our popular TB Intensive Workshop was taken on the road in April 2008! This provided an opportunity for local health care providers to participate in a course they might otherwise not have been able to attend. During the 2007 National TB Controller’s Association Meeting, TB Programs from Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, and the city of Detroit identified the need for a regional clinical intensive training. Toledo, OH was chosen as the training site because of its central location and ease of access for the four TB programs involved.

Months of planning – seven to be exact – through numerous emails, conference calls, and individual phone calls helped to make this vision a reality. It was through this extensive – and gratifying – planning process that we became better acquainted with our colleagues in the Midwest: Linda Burbank and Melinda Dixon (Detroit), Shameer Poonja and Sarah Burkholder (IN), Peter Davidson and Gail Denkins (MI), and Maureen Murphy (OH). This was truly a collaborative experience that helped to foster a stronger relationship between the RTMCC and each of the TB programs.

Using the RTMCC core course as a model, a TB Intensive Workshop was developed with input from the four TB programs to address the needs of clinicians currently managing TB patients in this geographic area. Topics included standard themes such as transmission and pathogenesis, treatment for LTBI and TB disease, TB-HIV co-infection, MDR-TB, and TB in children and adolescents. In addition, the following special topics were covered: lessons

learned from local outbreaks, a review of

changes in local epidemiology and TB

trends, and TB among immigrants and

refugees with an outline of new information

in the 2007 Technical Instructions

for Panel Physicians. A clinical discussion

of several cases was included to integrate

lecture component with practical

experiences in treating and managing

TB. In order to draw on existing TB

knowledge and local expertise in this

region, the TB medical consultant from

each program served as faculty for this

training. Additionally, faculty members

from various specialties were chosen

from state and local TB programs,

universities, and schools of medicine.

The two-day workshop, held on

April 17-18, 2008, was attended by a

total of 39 physicians and nurses from a

variety of workplace settings, including

local health departments, hospitals,

private practice, correctional medical

services, community health centers, and

college health centers.

Feedback about the course was very

positive. Based on the information

provided during the training, many

participants stated they anticipate making

changes in their practice, including:

- Review and revise current policies that impact standards of TB care

- Improve targeted testing practices for various patient populations

- Assess the way in which resources are allocated for TB

- Develop strategies for convincing patients to accept treatment of LTBI and complete therapy

As a result of the course, there was an overall increase in knowledge about TB. Specifically, participants were better able to define the difference between LTBI and TB disease, identify drug-drug interactions of rifamycins in the treatment of TB-HIV co-infected patients, list the environmental characteristics to consider during contact investigations, and understand how TB affects adults differently than children and adolescents.

The major strengths of the course were the content expertise of the faculty, the topics covered, and the interaction offered by the case studies. Members of the planning committee mentioned that participants from their area found the workshop to be helpful, comprehensive, and provided an opportunity to network with colleagues. Members of the planning committee and several course participants mentioned that this training should take place on a yearly basis. Truth be told, we would happily do it all over again. In fact, there are plans to offer a similar training for a different target audience in Fall of 2009 that would take place in the same geographic region.

Submitted by Anita Khilall, MPH, Training and Consultation Specialist NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

Staff Profile: Nancy G. Baruch, RN, MBA

Chief, Division of Tuberculosis Control, Refugee & Migrant Health, Maryland Department of Health & Mental Hygiene (DHMH)

(Left to right, back row) Adam Palmer (Refugee Health), Maureen Donovan, Cathy Goldsborough, Heather Rutz (TBESC), Tori Miazad, Dipti Shah (Refugee Health), Wendy Cronin (TBESC), Mark Miner (CDC Sr. PHA); (left to right, front row) Lien Nguyen, Nancy Baruch, Arlene Hudak, Vicki Randle; (not in photo) Sandra Matus.

Growing up in Michigan, Nancy Baruch became seriously interested in pursuing a career in healthcare, especially after reading an autobiography of Dr. Tom Dooley in elementary school. Growing up in a family of nurses (grandmother, mom, a couple aunts) and working as a nursing assistant at the local hospital while in high school (where she observed it wasn’t the doctors, but the nurses, who really made the difference in outcomes for most patients), she opted for a career in nursing. It first occurred to Nancy to pursue public health after doing a public health rotation during her senior year. She liked the independent thinking public health required, the myriad challenges, and the fact that in public health nursing you met lots of interesting people. She especially liked the respect and appreciation of clients when they met someone they felt cared. “Let’s face it, what public health nurses and outreach workers do in the field makes or breaks a TB program.” Maryland has been her home since she was a young adult.

Nancy’s career in tuberculosis control presented itself more or less serendipitously. “I had worked many years in the hospital setting as clinical nurse, manager, educator, and administrator. The opportunity

presented itself, I was looking for

something new, and yes, I had a

wonderful TB mentor, Sarah Bur. She

was visionary, dynamic, committed,

enthusiastic, and a great teacher for me.

From her, I learned that the function of

state program staff is to support what

local jurisdictions are doing. If you are

too focused only on what you want to

get accomplished, it won’t work. State level staff need to be cognizant that they are generally not out in the field doing the work of TB control. State program managers and staff exist to be of service to local health jurisdictions (LHDs), not the other way around.”

Nancy is now responsible for statewide programs related to TB, refugee, and migrant health; she oversees funding, education and training programs, and local program adherence to established guidelines for all three programs. All this happens only with the support of a wonderful team including two nurse consultants, a refugee health coordinator, one full-time and one parttime epidemiologist, one surveillance data manager for TB, one epidemiologist for refugee health, along with program, fiscal, and secretarial support staff. The TB program was, until recently, also supported by a Senior Public Health

Advisor assigned from CDC. While

much of the programmatic structure was

inherited, the ability to maintain it has

been key to providing LHD support. In

addition, the TB Epidemiological

Studies Consortium (TBESC) staff

report through this Division; DHMH is

Co-Principal Investigator on the TBESC

project in Maryland, partnering with

Baltimore City and the Johns Hopkins

School of Medicine. Nancy noted, “I am very proud of our state being selected as a TBESC site and the participation of both DHMH consulting and surveillance staff on various CDC TB workgroups. Encouraging staff to participate in national workgroups has strengthened our program in many ways, and also puts me in a better position to negotiate their travel to national meetings when restrictions are imposed.”

Reflecting on her career, she adds, “So far it has been a fantastic learning opportunity and I continue to learn all the time. I have been, and continue to be, impressed with the extraordinary work done by my colleagues in the field. I have seen TB in Maryland become largely a disease of the disenfranchised and the foreign-born, which presents unique challenges and demands.

When I first started working in this

field, TB was still largely a disease of the

elderly, infected much earlier in life; but

that no longer is the case. Populations

plagued by substance abuse and HIV

now contribute to the high TB rates, as

well as immigrant populations. As a

result, local health departments have

had to make many adjustments. Even

those jurisdictions with long-standing

multi-cultural and multi-lingual staff are

now caring for populations unknown to

most of us a decade ago, e.g., the Somali

Bantu."

What is Nancy like as a person?

"I tend to be pretty quiet, but enjoy being with family and friends. I also tend to be fairly patient, but don’t have much tolerance for the foolishness bureaucracies often create, and that can make working in a government job tricky at times. I wish we were not spending so much of our national resources on war. I wish we were not letting the fear of some potential ‘event’ drive public health resource decisions to such a large extent, versus dealing with the disease and want that already exists.” Outside of work, she says “I enjoy theater, opera and symphony. I love to garden, although I am somewhat limited by a postage stamp size yard. I like to read… especially history. I enjoy visiting local art galleries and museums. I love to visit the ocean when I can. And I like to wander through antique and junk stores—amazing things can be found!"

What are some of the top education and training priorities that you are working on right now?

"We are discussing how to provide for more advanced TB training beyond the basics. This is in response to requests from previously trained, seasoned staff – LHD nurses and doctors – who need sort of a TB 201, beyond basic TB 101 training. We are discussing this with our RTMCC and hope that the effort will help keep some local docs interested and on board with TB control. We are also planning for the introduction of the new RVCT and national TB reporting system (NEDSS TB–PAM) and for our statewide annual meeting in the Fall. We are finalizing our skin test training schedule which offers a series of trainings statewide following the academic year calendar; instruction will be provided by a nurse we contract with through a longstanding agreement between DHMH and a local community college."

Maryland has a well-developed internal training capability in the area of TB. What are your expectations and vision for TB education and training that will be provided by the MD State Department of Health?

"Our state has a long history of supporting local TB Control program staff. We have been fortunate in our ability to gain and keep the necessary funding to support nurse consultant staff that work closely with local programs and who are able to identify and respond to training needs, including on-site oneon- one training if needed. We have been extremely fortunate to be able to tap into the expertise and experience of local academic faculty who have an interest and background in TB; and we have been lucky in being able to work with a small, but critical, core group of local physicians who support our larger local TB programs."

How can we plan for who will run TB control in the future, as the current generation of TB leaders retires?

"We need to be more involved in ‘selling’ public health. In the past we could always recruit good people from local level positions; and as staff moved up, new graduates and people experienced in other public health programs took their place. Today, people feel public health does not pay enough or offer enough opportunities for professional growth. We need to get involved in pre-service education in schools to promote careers in public health, but also need to advocate for better salaries and professional growth opportunities."

The population of Maryland includes high risk groups that other states also serve: rural poor, migrant workers, and inner city. What are the challenges you face in controlling TB in these populations? How do you make sure your programs are effective?

"Availability of local resources is increasingly problematic. We emphasize treatment of cases to completion when they occur and have worked to improve contact investigations and treatment to completion of high-priority contacts. More and more jurisdictions are using 4 months of rifampin for the treatment of LTBI in individuals who are transient for various reasons. We have limited state funds to support incentives and enablers; and most of that money is now going to what I would call enablers—for example, supplementing county funds to pay someone’s rent for a couple months until they can return to work. We continue to receive state funds to support the purchase of TB medications for all local health departments. DOT is the standard of care with support for its use encoded in state regulation.” As part of the DHMH’s Office of Epidemiology and Disease Control Programs, Nancy’s staff participate in LHD site reviews every 18 months (or more often if needed) where a formal review of local TB programs takes place. They use this opportunity to support local staff concerns during their summations and in the formal write-ups to local health officers. For example, continued emphasis to local health officers on the importance of decreasing local TB staff time committed to TB testing for “political” versus public health reasons has had some measure of success. They also assist local staff dealing with migrant populations to connect with national TB organizations and have been able to support very limited targeted testing in some jurisdictions. Working with Baltimore City, they participate in a special workgroup set up to deal with the ongoing outbreak in the city’s homeless population. They were able to provide state TB funds to assist with the purchase of HEPA units for the larger City shelters, and supported an aggressive campaign by the City TB program to educate shelter staff about TB and basic case-finding techniques such as the use of cough logs. “Use your data and share it with the local jurisdictions. A standard session at our annual meeting includes a presentation of how the state has done in meeting

national TB program objectives and

where we need to focus our attention

over the next year.”

What do you find helpful in making you an effective trainer/educator?

“I think it is important to have indepth discussions about what formal training content should include in terms of identified needs, so you can take the information and make it pertinent to those you are trying to reach. You cannot teach effectively from algorithms alone. Being aware of local program differences is important. Timing is everything–for example, we routinely ask ourselves if we might potentially be conflicting with flu clinic season activities or pandemic flu exercises. Small regional meetings have been successful and are well received by local staff, but costs associated with travel may limit our ability to do them frequently. Conference calls and video-conferencing can also be effective means of getting the message out.”

“I encourage the use of the formal DHMH mechanism for notifying local TB staff about impending meetings, trainings, etc., because even though we could communicate this information less formally, I want the leadership at both state and local levels to be reminded of TB and to be aware of new training being offered. This is a little more work, but keeps TB on everyone’s radar screen. We encourage local staff to share their own experiences and have provided financial support for local staff to attend national meetings and national trainings when we can. For example, this summer no one from our office will be able to attend the TB-ETN national meeting in Atlanta; but we recruited an active member of our state’s program evaluation team to represent us. We also give an annual award to recognize excellent work in TB by an individual in the state.”

What about the value of training vs. technical assistance?

“While formal on-going training is important, we have found that in jurisdictions where TB occurs rarely, you

just have to walk people through the

process, be available for consultation,

and make sure you keep in touch

regarding follow-up.”

“Take the time to learn what the local TB issues really are and make an effort to address them. For example, even in a county that has not had a TB case in years, there is probably a local detention center that might be housing Federal detainees (a high-risk group); and perhaps that is a topic that should be addressed. Or maybe you need to provide the research information and program recommendations that local program staff can use to successfully engage other local decision makers, e.g., on the benefits of eliminating unnecessary TB screening within the local schools. Ask people what they need to know and keep in touch – don’t be someone they only hear from if the contact data is not right or if you want something.” How do you balance the ‘big picture’ with the ‘day-to-day’ when working with LHDs? “It is always a struggle to determine the best balance for formal training. I strongly believe that people need exposure to the bigger picture, both statewide and globally, and to be at least aware of the latest research.”

“However, I also think we need to be able to give people what they need day to day. If a jurisdiction is dealing with the first TB case in a while and the nurse assigned is new, I would start by asking if they have current guidelines available – don’t assume they were left on the shelf by previous staff. Ask about the medical provider and if it would be helpful to have a direct conversation with him or her. Ask if they have appropriate forms to document treatment and DOT. Review the standards of care and offer to assist with the contact investigation. Talk through their plans, as well as their capacity to implement them. Keep the lines of communication open. If the whole health department is in an uproar (e.g., related to a large contact investigation), get everyone who counts in on some of the initial conversations to help build trust. This is the type of support DHMH nurse consultants offer routinely to low incidence jurisdictions,

as well as to the revolving door of staff

assigned to work with TB in jurisdictions

where nurses wear multiple hats and

cross between programs. It is not formal

training, but is critical to program

success; and I suspect very few TB

programs, including ours, do a very good

job of documenting these activities.”

“I often remind providers who don’t see much TB that it is a very complex disease, and that as far as I am concerned, there is no such thing as a stupid question. If I don’t know the answer, I will do my best to find out and get back to people; and I tell them when to expect to hear from me.”

“Don’t assume that people read what you send them. Assume the opposite. If I work in a rural setting dealing with multiple programs and I get volumes of guidelines and e-mails from all sorts of state and CDC programs, I will probably be more inclined to read what is pertinent to what I have to deal with routinely, versus what I may not encounter for months. This is a fact of life that sometimes we tend to forget from the perspective of a state office. We need to remember it and not be offended when it occurs.”

“I also think when TB is an unusual occurrence, you need to be prepared to be an advocate for the staff at the local level. If they are working with a local physician who does not want to play by the rules, offer to intervene or assist them in a way that will preserve their working relationship. But do what it takes to get the recalcitrant provider on board with the plan of care.”

What does the future hold?

“I just read something the other day that I think is important to keep in mind. The baby boomers (myself included) learned their professions differently than the generation of new providers we are hoping to get interested in TB prevention and control. The new generation of health department staff will have grown up with computers, cell phones, I-pods, and other tools as routine implements of daily living and will expect to be able to use these tools in their daily work to communicate instantly with anyone, anywhere, anytime. The opportunities are endless,

the infrastructure costs potentially

significant for state and local programs,

and the challenges to adapt are very

real.”

“Some states have invested far more than others in technology infrastructure support to local jurisdictions, but we all need to be encouraging these discussions. It will be pretty hard to recruit and retain individuals totally comfortable with “instant messaging” to work in environments where someone higher up the chain of command has to “sign-off” on every message! Somewhere in this mix of new technologies, staid bureaucracies, lawyers, patients, and public health priorities there has to be a better balance than currently exists for the practitioners in the field, if we want to interest successive generations in public health careers.”

These are the words of a committed, thoughtful, forthright and supportive woman – someone we are lucky to count as a leader and colleague in the TB Control community.

Submitted by Bill L.Bower, MPH Director of Education and Training Charles P. Felton National TB Center at Harlem Hospital

back to top

Spotlight on the Behavioral/Social Science

Contribution to TB Control

Tuberculosis has long been viewed as resulting from the interplay of biological and social factors. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, popular belief and the medical community approached TB as a ‘social disease,’ and emphasized that the environmental and behavioral bases of TB had to be addressed before a patient could have a reasonable chance of being cured. In fact, the emergence and evolution of TB sanatoria might be understood as a debate over how to administer both the medical and the social cure for the disease. In more recent times, some have suggested that establishing DOT as the standard of care closes that debate prematurely, and sharply reduces the scope of the 'social cure' to the creation of a temporary mechanism that ensures the medical cure.

The 2001 Institute of Medicine report, “Ending Neglect,” called for the creation of “a program of research on behavioral factors related to TB treatment and prevention.” In response, the CDC’s DTBE convened the Tuberculosis Behavioral and Social Science Research Forum in December 2003. There are several reasons why such a research program could greatly assist TB control efforts. With the overall decline of TB disease in US-born populations, TB is increasingly found in individuals with one or more major challenges such as homelessness, substance abuse, or mental illness. Social and behavioral scientists and practitioners could help TB controllers in understanding these populations and devising effective means of reaching them.

Equally important is the persistence of high TB rates among the foreign-born. Despite their minority status in the US population, the foreign-born have represented the majority of cases with TB disease since 2001 and may represent around two-thirds of those being treated for Latent TB Infection. These individuals originate in countries with widely different TB beliefs and practices from the US. Again, behavioral and social scientists can help in understanding these beliefs, leading to the development of methods to modify

beliefs and change behavior to achieve

US public health goals.

Another important role for the

behavioral and social sciences is in the

promotion of treatment for Latent TB

Infection (LTBI). As traditional TB

control efforts have focused on the

identification and treatment of active

disease, TB controllers have become

accustomed to having – though only using as a last resort – the coercive power of public health law to force individuals to comply with a TB evaluation, accept DOT and complete treatment. Certainly, prudent TB programs have learned that “the carrot is better than the stick,” and have placed more emphasis on enticing

good adherence than threatening dire

consequences. Nevertheless, treatment

of active disease affords powers to TB

controllers that are not available when

managing LTBI treatment.

At the current time, completion rates

for LTBI treatment are abysmal, far below

the Healthy People 2010 goal of 85%.

In standard clinical practice, LTBI

treatment completion often falls below

50%. Nationally, even among infected

contacts to AFB-positive cases, only

about 70% start treatment for LTBI and

among these only 60% complete

treatment. An improvement in LTBI

completion rates will require a much

better understanding of patient beliefs

and behaviors:

- What motivates an individual to accept LTBI treatment despite conflicting information about its efficacy and the possibility of side effects?

- What motivates an LTBI patient to complete treatment despite a regimen longer than that for active disease,

other burdens related to long-term

pill-taking, and the lack of positive

benefits from symptom relief?

Both the TB control workforce and behavioral/social scientists continue to struggle with understanding and addressing the medical and social dimensions of the disease. We believe that an on-going dialogue between these two groups will further the goals of both TB control and behavioral/social science, and we hope that this series, ‘Spotlight on the Behavioral/Social Science Contribution to TB Control,’ will contribute to that dialogue. We welcome your comments to the ideas expressed above.

In subsequent issues, we will explore:

- The role that behavioral and social sciences have historically played in TB control;

- How behavioral/social science research informed HIV/AIDS interventions and implications for TB prevention and control;

- Recent findings from TB behavioral/ social science studies with practical programmatic applications; and

- Upcoming findings from specific TB Epidemiological Studies Consortium studies having a behavioral/social science focus and how these might be translated into practice. We welcome your comments and suggestions on how this Spotlight series might help to meet your needs.

Submitted by Paul Colson, PhD Program Director Charles P. Felton National Tuberculosis Center At Harlem Hospital

back to top

Northeastern Regional Medical Consultation Service, 2007

As an RTMCC, GTBI is tasked by CDC with strengthening medical consultation throughout the Northeastern US. Toward this end, since 2005 the GTBI has provided expert medical consultation to TB program medical consultants and other health care providers via 1-800-4TB-DOCS and email. In conjunction with each consultation, community providers are encouraged to contact TB program medical consultants with future requests for consultation. Educationally, GTBI has convened annual TB Medical Consultants Meetings for TB program medical consultants in the NE Region; conducted bi-monthly web-based grand rounds at which TB program consultants present difficult cases and receive feedback from colleagues; and provided training courses and webinars with a clinical focus. A Medical Consultation Webpage has also been developed to facilitate access to GTBI’s consultation services and resources.

To standardize the medical consultation process, GTBI developed a medical consultation protocol and data collection form and enters the results of each encounter into a database. To evaluate the medical consultation service, GTBI carries out quarterly quality assurance reviews on a sample of consultations and sends an end-user satisfaction survey to providers who request medical consultation services.

RESULTS

During 2007, GTBI consultants responded to 302 requests for consultation from health care providers in the NE Region. Of these, 162 from New Jersey were excluded from analysis, since GTBI staff serve as state medical consultants, providing a disproportionately large number of consultations to local HDs and hospitals, as well providers with pediatric-related questions.

Of the 140 requests from other areas in the Northeast Region, 42 % were from physicians, 49% from nurses, and 9% from other health care professionals. By incidence level, 9% of requests were

from providers in high TB morbidity

areas, 4% from medium morbidity areas,

and 86% from low morbidity areas.

Twenty-six percent of requests related to

children and 74% to adults.

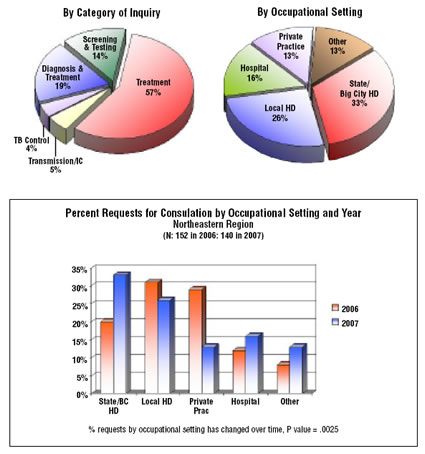

The two pie charts above present the

distribution of requests by category of

inquiry and by occupational setting of

health care provider.

In addition, requests for consultation

by occupational setting were compared

for 2006 and 2007 (see table above).

DISCUSSION

Overall, there were slightly fewer

requests for medical consultation during

2007 (140) compared with 2006 (152).

There were more requests from state and

big city health departments and fewer requests from local health departments

and providers in private practice. One

possible explanation for this is that local

health departments and private providers

are increasingly seeking medical

consultation from State/Big City TB

program consultants rather than GTBI.

However, this can’t be confirmed without surveying these providers. Nevertheless, if this explanation is correct, it would be consistent with GTBI’s efforts to strengthen medical consultation provided by TB programs and to encourage community providers seeking medical consultation to contact TB program consultants with future requests.

Submitted by Chris Hayden, Consultant NJMS Global TB Institute

back to top

Medical Consultation

Medical Consultation Services: NE RTMCC physicians respond to requests from providers seeking medical consultation through:

- Our toll-free TB Infoline: 1-800-4TB-DOCS and

- Email

During each consultation, the NE RTMCC physicians will advise providers of TB Program resources for consultation in their jurisdiction. In addition, TB programs will be informed of TB cases with public health implications.

Medical Consultant Web-Based Grand Rounds: Every other month, designated TB program medical consultants are invited to participate in a web-based TB case conference (or grand rounds). Consultants are encouraged to present challenging TB cases on which they would like feedback from their colleagues throughout the Region. The next conference is scheduled for June 26 at 4:00 p.m. TB program medical consultants who would like to present a case should contact Dr. Alfred Lardizabal at 973-972-8452 or lardizaa@njms.rutgers.edu.

back to top

NE RTMCC Training Courses

Courses are open to participants in the 20 project areas (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, NJ, New York State, New York City, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Washington DC, Detroit, Baltimore, and Philadelphia) which are served by the Northeastern National Tuberculosis Center.

Individuals outside of this region who wish to attend our training courses, should first contact their Regional Training and Medical Consultation Center to check whether the same or similar course is being offered. If this is not the case, the out-of-region participant may then register for this course.

Click here for the list of upcoming courses.

back to top

TB Program Training Courses

Click here for the list of upcoming TB program courses.

back to top

What's New

Cultural Competency and TB Care: A Guide for Self-Study and Self-Assessment Published in June 2008 by the NJ Medical School GTBI, this guide provides the TB program workforce and other healthcare providers with the basic knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for cultural competency in TB control activities. It explains how people’s beliefs around health affect their seeking of care, acceptance of diagnosis, and adherence with treatment recommendations. It also explores how to ask questions in a way that will elicit answers in a non-threatening, supportive way. The guide includes a self-assessment, as well as TB specific teaching cases. This guide was developed at the GTBI as part of series of cultural competency products developed by RTMCCS. Other RTMCCS as well as other TB programs with expertise in cultural competency contributed to the teaching cases in the Guide. This product can be accessed here.

Cultural Competency and TB Care: A Guide for Self-Study and Self-Assessment Published in June 2008 by the NJ Medical School GTBI, this guide provides the TB program workforce and other healthcare providers with the basic knowledge, skills, and attitudes necessary for cultural competency in TB control activities. It explains how people’s beliefs around health affect their seeking of care, acceptance of diagnosis, and adherence with treatment recommendations. It also explores how to ask questions in a way that will elicit answers in a non-threatening, supportive way. The guide includes a self-assessment, as well as TB specific teaching cases. This guide was developed at the GTBI as part of series of cultural competency products developed by RTMCCS. Other RTMCCS as well as other TB programs with expertise in cultural competency contributed to the teaching cases in the Guide. This product can be accessed here.

What Parents Need to Know About Tuberculosis (TB) Infection In Children Published in March 2008 by the NJ Medical School Global TB Institute (GTBI), this brochure provides parents with important information on TB infection in children. It is designed in a question and answer format with highlighted information for quick and easy readability. Information includes definitions of TB infection and disease, the diagnosis and treatment of LTBI, and tips on improving treatment. The brochure can be used by health care providers when providing education on LTBI to parents and then given to the parents. This product can be downloaded, printed and distributed at health department clinics or other health care facilities serving children with LTBI. The brochure can also be modified to include specific contact information for your clinic. The brochure can be accessed here.

What Parents Need to Know About Tuberculosis (TB) Infection In Children Published in March 2008 by the NJ Medical School Global TB Institute (GTBI), this brochure provides parents with important information on TB infection in children. It is designed in a question and answer format with highlighted information for quick and easy readability. Information includes definitions of TB infection and disease, the diagnosis and treatment of LTBI, and tips on improving treatment. The brochure can be used by health care providers when providing education on LTBI to parents and then given to the parents. This product can be downloaded, printed and distributed at health department clinics or other health care facilities serving children with LTBI. The brochure can also be modified to include specific contact information for your clinic. The brochure can be accessed here.

Diagnosis of LTBI in the 21st Century, 2nd Edition This scientific monograph, which was updated in 2008 by the NJ Medical School GTBI, discusses targeted tuberculin skin testing for latent TB infection as a strategic component of TB control. Specifically addressed are how to administer and interpret the tuberculin skin test with information about the test's specificity and sensitivity. There is also information about the Quanti- FERON®- TB Gold In Tube test and tuberculin sensitivity with mycobacteria other than M.

tuberculosis. This monograph is

certified for continuing medical and

nursing education through the

completion of a post-test and

evaluation located at the end of the

document. This product can be

viewed here.

Diagnosis of LTBI in the 21st Century, 2nd Edition This scientific monograph, which was updated in 2008 by the NJ Medical School GTBI, discusses targeted tuberculin skin testing for latent TB infection as a strategic component of TB control. Specifically addressed are how to administer and interpret the tuberculin skin test with information about the test's specificity and sensitivity. There is also information about the Quanti- FERON®- TB Gold In Tube test and tuberculin sensitivity with mycobacteria other than M.

tuberculosis. This monograph is

certified for continuing medical and

nursing education through the

completion of a post-test and

evaluation located at the end of the

document. This product can be

viewed here.

2008 Tuberculosis Technical Instructions for Civil Surgeons Published by CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine, the May 2008 TB Technical Instructions replace the TB section in the 1991 Technical Instructions (TIs), and are to be used by Civil Surgeons effective May 1, 2008 in screening immigrants already in the US and who are applying for US citizenship. Significant changes in the May 2008 TB Technical Instructions are summarized on pages 1 and 2 of the Technical Instructions document. The entire set of instructions, a memo to Civil Surgeons, and FAQs are posted at the following website.

2007 Technical Instructions for Tuberculosis Screening and Treatment for Panel Physicians At the end of 2007, the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine (DGMQ), along with the CDC Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, updated the Technical Instructions which are used by panel physicians in screening for TB among persons overseas who are applying for US immigration and non-immigrants who are required to have an overseas medical examination. The Technical Instructions document and a comparison of the 1991 and 2007 Instructions can be accessed here.

Slide Set – Epidemiology of Pediatric Tuberculosis in the United States, 1993-2006 Published by CDC’s Division of TB Elimination in April 2008, this slide set summarizes trends in the magnitude and distribution of pediatric TB over a 14 year period. It can be accessed here.

Shelters and TB: What Staff Need to Know, Second Edition Published by the Francis J. Curry National TB Center (CITC), this 18-minute training video is designed for homeless shelter staff and explains how to prevent the spread of TB in homeless shelters. It includes information on how TB is spread, what to do if staff suspects someone with TB, how to develop and implement a TB infection control policy, and how shelters and health departments can collaborate. This video can be ordered or viewed on line here.

Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Survival Guide for Clinicians, Second Edition First released in 2004 by the CITC, this recently updated Guide contains information and userfriendly tools and templates for use by any clinician who participates in the management of patients with drug-resistant TB. It can be accessed at this website. and new information includes

- Updated epidemiology of TB and MDR-TB

- Treatment for XDR-TB

- Information about interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs), new blood tests for LTBI

- Updated medication fact sheets

- New information about drug interactions

- Updated listings of MDR experts, laboratories, and international resources

TB Contact Investigation in Jail: A Facilitator Guide Published by the CITC in May 2008, this facilitator-led training product is designed for use by correctional liaisons who facilitate the training of jail and health department staff who conduct TB contact investigation in the jail setting. The Guide presents information about the risk of TB transmission in a jail setting, how TB can affect jail inmates and employees, and how to perform a TB contact investigation in jail. Training materials include PowerPoint presentation slides, speaker notes, exercises, case studies, questions/answers key, and a master copy of all participant materials for duplication purposes. The Guide can be accessed here.

TB Program Evaluation Handbook Published in hardcopy by CDC in 2006, this handbook provides an in-depth introduction to TB program evaluation that has been tailored for staff of state and local TB programs who are charged with leading self-evaluation efforts. It can now be accessed online.

Promoting Cultural Sensitivity: A Practical Guide for Tuberculosis Programs That Provide Services to Hmong Persons from Laos Recently published by CDC’s Division of TB Elimination, this is one guide in a series that aims to help tuberculosis (TB) program staff provide culturally competent TB care to some of our highest priority foreign-born populations. Other guides in the series focus on people from China, Mexico, Vietnam, and Somalia. The guide is designed to increase the knowledge and cultural sensitivity of health care providers, program planners, and any others serving Hmong people from Laos. The ultimate aim is to foster culturally competent TB care and services for the Lao Hmong in the United. It can be accessed here.

back to top

On the Lighter Side - Match the Baseball Player with Bio Sketch

| _____ Rico Carty |

A. One of the most popular figures in St. Louis baseball history, he was in a Cardinals' uniform in seven decades, starting during World War II. As a player, he was a gritty second baseman with a strong arm and a good bat. He overcame great adversity when he rebounded from tuberculosis in 1960, after the illness forced him to miss all but five games the previous season. As a manager, he led the Redbirds to two World Series and one World Series title, skippering the team in four different decades. His 14th-inning home run won the 1950 All-Star Game for the National League. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1989. |

| _____ Carlos Guillen |

B. The greatest pitcher in Giants’ history (1900-1916), he was an idol to his fans. A clean-cut, well spoken gentleman, he was a rare breed in the early days of 20th century baseball. The righthander won more games than any other pitcher in National League history and was one of the first five players elected to the Hall of Fame. In 1918, he enlisted in the US Army and developed TB while in France. Although he returned to serve as a coach for the Giants for 2 years, he continued to struggle with TB and eventually died in Saranac Lake Sanitorium in 1925. |

| _____ Red Schoendienst |

C. Born in Venezuela, he played for the Seattle Mariners from 1998-2003 and for the Detroit Tigers since 2004. Midseason in 2001 this hard-hitting third baseman lost 20 pounds and coughed up blood, but kept playing another 2 1/2 months before being diagnosed with TB. The Mariners made it to the playoffs, but eventually flamed out with out his presence. He made a full recovery and went on twice to be named to the All Stars (2004 & 2007) |

| _____ Christy Mathewson |

D. High on any list of the great natural hitters, the powerful Dominican hit .330 as a rookie in 1964, losing the batting crown to Roberto Clemente. TB sidelined him for the entire 1968 season; he spent five months in a sanitorium. Incredibly, he returned to hit .342 in 1969, despite seven shoulder dislocations. He played 11 years with the Milwaukee/Atlanta Braves and retired in 1979 with the Toronto Blue Jays. He led the National League in batting in 1970. |

back to top

Links - Other TB Resources

Division of Tuberculosis Elimination

The mission of the Division of Tuberculosis Elimination (DTBE) is to promote health and quality of life by preventing, controlling, and eventually eliminating tuberculosis from the United States, and by collaborating with other countries and international partners in controlling tuberculosis worldwide.

TB Education and Training Resources Website

This website is a service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. It is intended for use by TB and other healthcare professionals, patients, and the general public and can be used to locate or share TB education and training materials and to find out about other TB resources.

TB Education & Training Network (TB ETN)

The TB Education and Training Network (TB ETN) was formed to bring TB professionals together to network, share resources, and build education and training skills.

TB-Related News and Journal Items Weekly Update

Provided by the CDC as a public service, subscribers receive:

- A weekly update of TB-related news items

- Citations and abstracts to new scientific TB journal articles

- TB conference announcements

- TB job announcements

- To subscribe to this service, click here

TB Behavioral and Social Science Listserv

Sponsored by the DTBE of the CDC and the CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN), this Listserv provides subscribers the opportunity to exchange information and engage in ongoing discussions about behavioral and social science issues as they relate to tuberculosis prevention and control.

New England Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Website

At the beginning of 2005, the six New England TB Programs joined together to promote a regional approach to TB elimination. This web site represents a step toward building collaboration, exchanging experiences and practices, and enhancing program capacity.

Other RTMCCs

The Curry International Tuberculosis Center serves: Alaska, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, Federated State of Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Republic of Marshall Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Republic of Palau.

The Heartland National Tuberculosis Center serves: Arizona, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin.

The Southeastern National Tuberculosis Center serves: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

back to top

Key Contacts

- Lee B. Reichman, MD, MPH - Executive Director

- Reynard J. McDonald, MD - Medical Director

- Bonita T. Mangura, MD - Director of Research

- Eileen C. Napolitano - Deputy Director

- Nisha Ahamed, MPH, CHES - Program Director, Education and Training

- Chris Hayden - Northeastern Spotlight Editor

- Alfred S. Paspe - User Support Specialist/Webmaster