Dear Colleague:

Dear Colleague:

I am happy to report that as of January 2010, the Global TB Institute began its second five year cooperative agreement cycle as the CDC funded Regional Training and Medical Consultation Center for the northeastern United States. During our first five year cycle we worked together with you to provide more than 140 separate training events, for a total of 1125 hours of training that reached over 7500 participants. Now, with the start of the new cycle, we are looking forward to continuing our work with TB Programs throughout the northeast to meet the TB training, education, and medical consultation needs in the region.

As part of this process, CDC has again asked us to conduct a regional needs assessment on TB training and medical consultation needs in the region. Some of you may have been involved in our 2005 needs assessment. The 2010 needs assessment will be similar, as it will include online surveys as well as interviews with key TB program staff. For this needs assessment however, all four RTMCCs will use standardized tools. We are currently involved in working with CDC and the other RTMCCs to develop these tools and will reach out to TB programs during the process of development, and then of course will send the surveys out far and wide to gather input from you all, the TB and public health workforce, on your TB training and medical consultation needs!

This issue of the Northeastern Spotlight features a description of a series of TB Updates conducted last year in Massachusetts focusing on TB and Substance Use as well as our regional TB Intensive held in Fort Wayne, Indiana. This issue also includes the next Behavioral/Social Science installment in our series, which highlights Task Order 12: Providers Serving the Foreign Born. In addition, we feature an engaging and informative profile of Jill Fournier, the TB Program Coordinator in New Hampshire. We are also including an article on the CDC launch of TB GIMS, the TB Genotyping Information management system in spring of 2010 and a very informative article on how TB Programs can use the principles of Risk Communication.

As always, thanks for all your efforts, and we look forward to working with you in 2010 and during the next five years!

Lee B. Reichman, MD, MPH

Executive Director

Northeastern RTMCC and the

Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

Current Behavioral/Social Science Studies in Tuberculosis – Part 3: Providers Serving the Foreign Born

The last two installments of this column have focused on behavioral studies being conducted through the Tuberculosis Epidemiological Studies Consortium (TBESC) – specifically, Task Orders 13 and 9. The subject of this installment, Task Order 12, is motivated by the same concern as Task Order 9 – improving outreach and treatment to the foreign-born – but focuses instead on the providers who serve this group. As with other Task Orders (TOs), the co-principal investigators for TO 12 include experts from academia (Carey Jackson, University of Washington), public health (Jenny Pang, Seattle & King County), and CDC (Nickolas DeLuca). I served as an advisor for this project.

Task Order 12 – Primary Care Management of Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) and Tuberculosis Disease Among Immigrant Populations: A Study of Barriers and Facilitators

As mentioned in the last installment, foreign-born people represent the majority of TB cases in the US (CDC 2008) and as indicated by several recent studies, a large majority of persons recommended for LTBI treatment (Horsburgh et al in press; Sterling et al 2006). TO 12 focused on primary care providers serving people from Mexico, the Philippines, and Vietnam, the three countries with the highest TB incidence among immigrants. The study was conceived in two phases: the first phase entailed formative research to determine TB knowledge, attitudes, and practices of primary care clinicians serving the target groups. Using information from the first phase, an intervention to change provider behavior was designed and tested in the second phase.

Phase 1 – Formative Research

In the qualitative assessment phase conducted in 2005 – 2006, a total of 80 health care providers were interviewed in groups or individually in six regions – Honolulu, Seattle, San Francisco, Orange County CA, Dallas-Fort Worth, and Boston. To participate, providers had to work in primary care settings (family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, women’s health), have at least 25% of patients be foreign-born, have at least 3 years of clinical practice with at least one year at their current sites, and not be employed by a public health department.

Providers reported a number of factors they felt facilitated effective LTBI screening and treatment:

- having a designated staff person to manage TB screening and treatment adherence

- maintaining a good relationship with the local TB clinic

- making disease prevention and health promotion part of the clinic’s culture of care

Factors and attitudes working against effective LTBI care included:

- believing that patients’ positive TST results were solely due to past BCG infection

- not taking TB seriously because it was so rarely seen

- financial disincentives for screening and treating LTBI

- lack of staff to ensure or encourage LTBI treatment adherence

- LTBI treatment viewed as “too long”

Phase 2 – Intervention to Alter Knowledge and Attitudes

Phase 1 results were used to design an educational intervention to modify knowledge and attitudes among providers serving the foreign-born. An educational intervention was chosen because the Phase 1 primary care providers were not clear on the definition of risk groups for TB (including HIV, diabetes, and other co-morbid conditions), TST interpretation (considering BCG vaccination, HIV, and recent contact), and guidelines suggesting that age should no longer be considered a factor in prescribing LTBI treatment.

A pre-test survey was administered to 92 primary care providers (who were selected using the same criteria as Phase 1 but with different individuals), followed by a 1-hour didactic session delivered by a local TB expert and then a post-test survey. Responses to knowledge items generally improved from pre- to post-test, becoming more consistent with CDC/ATS guidelines. Participants showed increased knowledge regarding TST interpretation, risk groups, and the effectiveness of isoniazid therapy for all age groups unless contraindicated.

However, some items revealed on-going issues consistent with those identified in Phase 1. Private physicians continued to be concerned about reimbursement for LTBI care and the financial incentives for ensuring LTBI treatment completion. Providers who worked in federally qualified health centers and public hospitals, in contrast, were more likely to encourage patients to initiate LTBI treatment and to access resources for billing and nursing support. Providers also pointed out the difficulty in explaining the need for LTBI treatment, suggesting that more attention be given to patient education materials.

Conclusion

Findings from Task Order 12 demonstrate the effectiveness of an educational intervention to modify basic TB knowledge among primary care providers serving foreign-born patients. It also underscores the limitations of an educational approach in addressing issues such as financial and logistical limitations in screening and treating LTBI in private practice settings, and overcoming attitudes about the need for LTBI treatment among individuals who received BCG vaccination.

This column’s next installment will focus on Task Order 11.

Submitted by Paul Colson, PhD, Program Director

and Julie Franks, PhD, Health Educator and Evaluator

Charles P. Felton National TB Center at Harlem Hospital

Citations:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in Tuberculosis -- United States, 2007. MMWR 2008; 57:281-285.

Horsburgh CR, Goldberg S, Bethel J, Chen S, Colson P, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Hughes S, Shrestha-Kuwahara R, Sterling TR, Wall K, Weinfurter P, TBESC. In Press. Latent tuberculosis infection treatment acceptance and completion in the United States and Canada. Chest.

Sterling TR, Bethel J, Goldberg S, Weinfurter P, Yun L, Horsburgh CR, Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium. The scope and impact of treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in the United States and Canada. Am J Res Crit Care Med 173(8):927-31, 2006.

back to top

CDC Division of TB Elimination Announces Launch of TB GIMS in Spring 2010

The National Tuberculosis Genotyping Service started in 2004 when state laboratories from all TB programs in the United States voluntarily started submitting Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates from culture-confirmed patients to CDC-contracted laboratories in Michigan and California. TB genotyping is a laboratory-based approach used to analyze the genetic material of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in order to distinguish different strains of M. tuberculosis. Typical applications of genotyping include:

- Discovering unsuspected transmission relationships between patients

- Identifying unknown or unusual transmission settings, such as bars or clubs, instead of traditional settings like home and workplace

- Uncovering interjurisdictional transmission

- Establishing criteria for outbreak-related case definitions

- Identifying additional persons with TB disease involved in an outbreak

- Determining completeness of contact investigations

- Detecting laboratory cross-contamination events

- Distinguishing recent infection (with development of disease) from activation of an old infection

Use of genotyping results has significantly improved our understanding of TB transmission nationally and within the Northeastern region. However, since its inception in 2004, managing genotyping data has been a challenge to individual TB programs, particularly in monitoring data for significant clusters and attaching individual patient clinical and demographic surveillance information to genotyped isolates. Although some informal agreements have been arranged between states, no comprehensive national TB genotype database has been available. Given the mobility of TB patients and the tendency for outbreaks to involve multiple states, the National TB Controllers Association (NTCA) has advocated for the ability to readily view the national picture of genotype clusters, automate cluster identification, and further characterize clusters based on the clinical and demographic makeup of clustered TB patients.

On December 9th, 2009, the CDC Division of TB Elimination announced the launch of the “TB Genotyping Information Management System” (TB GIMS) in spring of 2010. This will be a free web-based software program available to state/TB project area TB controllers. TB GIMS will link genotyping results to the epidemiologic data from surveillance reports. Queries and reports can then be generated to compare genotyping results locally and nationally. Ultimately, TB GIMS will generate alerts or notifications of suspected recent transmission and help identify TB clusters and direct public health action. Specifically, TB patient surveillance information will be linked to genotype results in TB GIMS by the following process:

- The TB lab from each state/TB project area submits isolates to contract labs in Michigan or California and enters initial isolate information into TB GIMS. Only one isolate per patient is entered.

- Genotype results are entered into TB GIMS (now both state/TB project area TB programs and genotyping labs have access to information).

- CDC lab updates and manages information on Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains/lineages.

- A “super user” assigned by the state/TB project area adds the state case number that will link the genotype results with the TB patient surveillance data (i.e. the Report of Verified Case of TB).

- CDC will complete the linkage between surveillance and genotyping information.

- Reports and maps will be generated at the patient level for isolates that have been linked with a state case number.

Combining patient-level data with genotyping results in one accessible, national web-based system will be a tremendous advantage for TB Controllers. Because confidentiality and security will be crucial to the success of TB GIMS, access will be restricted to authenticated and approved users in the TB Control community, and data will not be available to the public. Authorized users will be designated only by state/TB project area TB controllers or their designees. “Super users” will be authorized to edit or export patient-level data from their jurisdiction. For more information on TB GIMS and patient confidentiality, visit http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/statistics/TBGIMS.pdf

CDC is planning TB GIMS training for the spring. The training will enhance each TB program’s ability to:

- Integrate genotyping analysis into routine TB prevention and control activities

- Identify transmission patterns and perform cluster investigations stretching back over years/decades

- Analyze ongoing transmission temporally, geographically, and by risk factors

The timeline for roll-out of TB GIMS is as follows:

- January 2010 – registration to access TB GIMS begins

- March 2010 – state laboratories begin submitting isolates using TB GIMS

- March 2010 – state super users begin linking surveillance and genotyping data

- March-April 2010 – CDC launches TB GIMS live webinar training and pre-recorded webinars for state/TB project area TB control programs

For questions, please email tbgims@cdc.gov.

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of TB Elimination, 2009. TB Genotyping Information Management System (TB GIMS) Fact Sheet. November, 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/statistics/TBGIMS.pdf

Griffin, P. “Endorsement letter from the National TB Controllers Association” dated December 1, 2009. NTCA. http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/factsheets/statistics/TBGIMS.pdf Accessed December 28, 2009.

Navin, T. “Dear Colleague” letter dated December 9, 2009. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of TB Elimination.

Contributors:

Lynelle Phillips, RN, MPH; Consultant, Heartland National TB Center

Smita G. Chatterjee, MS; Research Epidemiologist, Division of Tuberculosis Elimination, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, CDC

back to top

Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication: What TB Programs Need to Know

Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (also known as CERC) combines the urgency of disaster communication with the need to communicate risks, benefits, and needed action to stakeholders, healthcare providers, media, and the general public. CERC differs from risk communication in that:

- Communication decisions on how to respond to the crisis must be made within a short time constraint;

- These decisions may be irreversible;

- Outcomes of the decision may be uncertain; and

- Decisions may need to be made based on less than perfect or incomplete information.

Overall, CERC can minimize some of the harmful human behaviors that are known to arise during a crisis.

How can TB Programs use CERC?

When people are faced with a crisis or emergency situation, they take in information differently, process information differently, and act on information differently. CERC principles can be extremely useful to TB programs during a TB outbreak or high profile event. When an outbreak occurs, there is often a sense of panic, fear, confusion, anxiety, and helplessness. Using CERC principles to disseminate information can help the public cope and instill a sense of empowerment within the community. Feeling empowered to take action reduces the likelihood of feeling victimized and alleviates fear. The use of an “action message” can provide people with the feeling that they can take steps to improve a situation. During a TB outbreak, effective communication provides information on useful resources for those affected. For example, during a TB outbreak, providing information on local testing sites to go for TB testing is a useful action message.

Five CERC principles to communicate messages successfully during a crisis or TB outbreak:

- Develop a solid communication plan Your TB program’s outbreak communication plan should be fully integrated into the overall program’s emergency response plan. This plan should address all of the roles, responsibilities, and resources involved in providing information to the public, media, and partners during a TB outbreak. It should include such elements as a signed endorsement from the program’s director, regional and local media contact, and staff responsibilities. The communication plan should be seen as a resource of information. In general, the public tends to judge the success of a response by the success of its communication plan during a crisis.

- Be the first source of information It is important for the TB program to be the first source of information during a TB outbreak. The public sees the speed of useful information as a marker of preparedness. In addition, when people seek information about something unknown, the first message they receive tends to carry the most credibility. Therefore, it is important for the TB program to be the first source of information. For example, if your TB program’s first message is: “Only people who spent extended time with the student with TB are at risk of developing the disease. We are contacting those persons to ensure they are tested”, the audience will remember this message and accept it. Later, if a subsequent message from another source says: “Everyone should be tested for TB”, the audience will compare the second message to the first message. They are more likely to accept the first one because it is from a credible source and it was the first message received.

- Express sympathy early Empathy is the ability to understand what another human being is feeling. Research has shown that it should be expressed within the first 30 seconds of message delivery. This is a very challenging but critical step in crisis communication. Empathy shows sincerity to the public, and also helps the public hear the message. For example: “We recognize that you are anxious about the recent TB outbreak and we understand your concern. We are available to answer questions that you may have about the situation.”

- Show competence and expertise Research shows that people believe that individuals in professional positions within respected organizations are experienced and competent. It is important to maintain the highest level of expertise as a way of fostering trust. When a TB outbreak occurs, provide necessary information to ensure the affected audience understands the situation. For example, provide the public with information on how TB is transmitted along with the signs and symptoms of the disease.

- Remain honest and open In many cases, when information is being disseminated following an outbreak, everyone assumes that some information is being held back. For this reason, it is best to let the public, stakeholders, and the media know that they will be updated with information as it becomes available. For example: “Currently, we do not know if there are others who may have been infected or have TB disease. We will continue to update you as we learn more.”

Message Planning

The content as well as the method of message delivery during an outbreak are extremely important. Dissemination of appropriate messages to the community helps to reduce fear and anxiety. When developing CERC messages, it is critical that:

- Affected audiences are identified;

- Key messages are developed with supporting facts included; and

- Effective dissemination channels are used.

When people are faced with a crisis, they want to receive messages that are accurate, helpful, timely, empathetic, short, and concise. Messages disseminated in response to a TB outbreak should follow the STARCC principle.

Messages should be:

- Simple

- Timely

- Accurate

- Relevant

- Credible

- Consistent

Working with the Media

When a TB outbreak or high profile event occurs, it is very likely that it will generate media interest. Use the media to your advantage! The media can reach a large number of people quickly and can assist you with message dissemination. The media is attracted to messages that are convenient, simple, visual, and emotional. To assist with developing messages for the media, the key is to identify the Single Overriding Communication Objective, also known as the SOCO. The components of the SOCO include:

- Key point or objective (e.g.-What is the most significant point in the message?)

- 3-4 facts or statistics (e.g.-How many people may have been affected?)

- The primary and secondary audience (e.g.-Who are the populations of interest?)

- One key message (e.g.-The patient is currently undergoing treatment.)

- Contact information (e.g.-Who can be reached for more information?)

A SOCO worksheet is available in the publication: “Forging Partnerships to Eliminate Tuberculosis: A Guide and Toolkit” on the CDC website at http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/guidestoolkits/forge/default.htm. View a Sample Single Overriding Communications Objective (SOCO) Worksheet (MS Word - 36kb)i

A spokesperson to represent your TB program should be identified to interact with the media during an outbreak. Having a spokesperson gives an identity to your program, and shows competence and expertise. Your spokesperson should be well trained, have the ability to effectively connect with the audience, and communicate information about an outbreak. It is important to include your spokesperson in message development. This helps to ensure that he or she “owns” the statements and will help convey confidence, believability and trust. Your spokesperson should not only know the needs of the TB program, but should also show empathy to the affected audience. Your spokesperson should not: be defensive, express personal opinions, over-reassure nor use humor, jargon, one-liners, or clichés.

Partnerships and Communication

Joining forces with your partners creates an opportunity to foster respect, trust, and commitment with your target audiences. In crisis communication planning, it is important to identify and involve your partners and stakeholders to gain access to their skills and resources. Partners can assist with developing messages that are appropriate, sustainable, and effective for the audience. When a TB outbreak occurs, providing timely and accurate information to key internal and external partners and stakeholders helps to strengthen existing relationships. To learn more about partnership planning, access the publication: “Forging Partnerships to Eliminate Tuberculosis: A Guide and Toolkit” on the CDC website at http://www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/guidestoolkits/forge/default.htm and view Planning with Partners: Moving from Goals to Effective Action Checklist (MS Word - 34kb)ii

Evaluation of Messages

The key to communicating effectively during an outbreak is to evaluate messages at various stages of dissemination. Seeking audience feedback is useful to refine the communication strategy when necessary, and to improve the effectiveness of the messages.

Evaluation methods that can be used to evaluate risk communication messages are:

- Formative Evaluation Messages should be ‘pilot-tested’ prior to dissemination to the target audience. After messages are developed, share them with your internal and external partners to determine if the messages are clear and comprehensive. Feedback obtained can then be used to revise and improve the messages before they are disseminated widely.

- Process Evaluation This examines the procedures and tasks involved in implementing an activity, such as the channels of delivery and the number of messages disseminated. After the messages are disseminated, it is important to monitor the methods of message delivery (e.g., on-line, print distribution). In addition, also determine the number of materials distributed (e.g., number of factsheets disseminated to the public, number of public inquiries received as a result of the message).

- Outcome Evaluation This form of evaluation assesses the effectiveness of the messages being disseminated. The effectiveness can be determined by changes in the behavior of the target audience as a result of the messages received. Outcome evaluation can obtain descriptive data and show the immediate effects of the messages disseminated. For example, after disseminating messages following an outbreak, obtain data on the affected audience coming in for testing.

- Impact Evaluation This type of evaluation focuses on the long term effects of the messages being disseminated during an outbreak, such as number of persons with TB infection or TB disease identified. Impact evaluation is harder to accomplish because it is difficult to separate the impact of disseminated messages on the audience from the effects of other activities.

To learn more about evaluation of risk communication programs, view Evaluation Primer on Health Risk Communication Programs on the CDC website at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/risk/evalprimer/types.html.iii

Submitted by:

Ijeoma Agulefo, MPH

Health Education Specialist

Communications, Education and Behavioral Studies Branch

Division of TB Elimination

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References:

iCenters for Disease Control and Prevention website, 2007. Forging Partnerships to Eliminate Tuberculosis: A Guide and Toolkit. [Online] (Page last updated 1 June 2009). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/TB/publications/guidestoolkits/forge/ToolkitWord.htm [Accessed on February 5, 2010].

iiCenters for Disease Control and Prevention website, 2007. Forging Partnerships to Eliminate Tuberculosis: A Guide and Toolkit. [Online] (Page last updated 1 June 2009). Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/TB/publications/guidestoolkits/forge/ToolkitWord.htm [Accessed on February 5, 2010].

iiiAgency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry website, 1997. Evaluation Primer on Risk Communication Programs: Types of Evaluation. [Online] (Page revised May 1997). Available at: http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/risk/evalprimer/types.html [Accessed on February 8th, 2010].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication. October 2002.

back to top

Staff Profile: Jill Fournier, RN Program Manager, New Hampshire TB Program

A true New Englander, New Hampshire TB Program Manager Jill Fournier was born on Cape Cod and raised in Enfield, Connecticut before moving to New Hampshire twenty-five years ago. She started out as a hospital nurse working on the surgical floor and the orthopedics and obstetrics wards, until one day when she saw an advertisement in the newspaper for an immunization Public Health Nurse.

A true New Englander, New Hampshire TB Program Manager Jill Fournier was born on Cape Cod and raised in Enfield, Connecticut before moving to New Hampshire twenty-five years ago. She started out as a hospital nurse working on the surgical floor and the orthopedics and obstetrics wards, until one day when she saw an advertisement in the newspaper for an immunization Public Health Nurse.

“I thought it sounded interesting, and my children were older and I felt they would benefit from my having a more ‘normal’ schedule, so I decided to go for an interview,” Jill said. “I got the job, and have been a Public Health Nurse for the state of New Hampshire ever since. The thing I enjoy about public health is the variety of what you deal with and how you’re busy all the time with different issues. For example, last spring all of our communicable disease nurses were busy with the H1N1 epidemic, so I was out in the field skin testing refugees. You never know what will happen next or what you’ll be called upon to do!”

After 13 years in the immunization program, Jill became the TB Program Manager for New Hampshire because it gave her the opportunity to continue her professional growth and do supervisory work, as well as being a nice opportunity to learn something new. “One of the first things I did was to brand the TB Program. In New Hampshire we only have three city health departments, so most everything is done at the state level. We don’t have TB clinics, so all patients are seen privately with public health follow-up. This meant that it was important for private providers to be aware of the TB program and know how to get in touch with us, but when I started we found that there was very low awareness that we even existed. So we created an informational brochure and slide set with a teal color and distributed this to providers throughout the state.” Now whenever the New Hampshire TB Program creates a new material, it incorporates the teal color into the finished product to connect everything it does and help build recognition.

New Hampshire is one of the few states to make latent TB infection (LTBI) a reportable condition. Part of Jill’s duties involve looking over incoming reports of LTBI, in order to determine if a patient is at high risk and in need of public health follow-up. The New Hampshire TB Program has an LTBI database that goes back eighteen years, and one of Jill’s projects involves collaborating with CDC to link the LTBI data to active cases. “The Centers for Disease Control recently made a site visit to take a look at our LTBI database,” Jill said. “As the number of active cases drops, the pool of people with LTBI is going to become increasingly important.”

One of the advantages to working in a small state is the ability to build relationships with key players. “You keep a lot of the same contacts despite moving to a different position. Now I’m trying to collaborate more with the HIV/AIDS and refugee programs, and it’s easier because I already know some people in these departments. And everyone working in the same building certainly helps!”

Lisa Roy and Jane Bertolone, the Health Educator and Program Assistant with the New Hampshire TB Program, commented on Jill’s generosity. “She’s always doing special things for the staff and for TB meetings. And she takes a lot of pride in her work with TB, and has a strong attention to detail."

While she may be relatively new to the TB world, Jill is increasingly involved with planning and policy on the regional and national levels. She was recently elected to the Steering Committee for the TB Program Evaluation Network, and presented her evaluation project from the perspective of a low incidence state at the first annual TB-ETN/TB-PEN Conference. Jill is also actively involved with the New England TB Consortium, and is currently helping plan a cohort review training for the New England State TB programs. “I hope to be even more involved in the future, as I continue learning the ropes of TB.”

Jill lives in quaint Henniker, NH, which a wooden sign in town proclaims is The Only Henniker on Earth. She was appointed Health Officer for Henniker in 2002, where she focuses on emergency preparedness issues for the town. Jill has two cats, Comet and Superstitious, as well as a rescue dog from a high-kill state. “She came from a high-kill shelter in Kentucky, so that’s why she’s named Dixie.” In her spare time, Jill enjoys quilting and reading, as well as generally hibernating in the winter. “I’m not liking the cold as much as I used to, but at least it’s a good time to do sewing!”

Jill has three children, and says she likes to cook “because my children like to eat!” The TB Program also benefits from Jill’s cooking skills. “Jill bakes homemade treats for almost every TB meeting and for no occasion at all,” says Lisa Roy. “She might spend the entire evening prior to our meeting baking.” With Jill in the mix, the New Hampshire TB Program sure sounds like a great place to be!

Submitted by:

Nickolette Patrick, MPH

Training and Consultation Specialist

NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

Tuberculosis Control in Substance Abuse Treatment Centers: Training the Workforce about a New Policy

In the fall of 2009 the Northeastern Regional Training and Medical Consultation Center cosponsored a series of trainings focused on TB control in substance abuse treatment centers in collaboration with the Massachusetts Division of TB Prevention and Control, the Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Abuse Services (BSAS), and the New England Addiction Technology Transfer Center (ATTC).

The trainings focused on a new policy for Tuberculosis control in substance abuse treatment centers that had been released by the Massachusetts Division of TB Prevention and Control and BSAS. This policy was the result of a collaborative partnership between the two entities, and called for TB screening, education, and referrals, as well as targeted TB testing in substance abuse treatment centers in Massachusetts. To help ensure this policy was properly implemented, BSAS mandated that at least one person from each substance abuse treatment facility attend a training about the new policy.

The past year has seen a real growth in collaborative relationships between the RTMCC and other federally-funded training centers (including AIDS Education Training Centers, the Addiction Technology Transfer Center Network, Title X Family Planning Training Centers, STD/HIV Prevention Training Centers, and the Viral Hepatitis Network). These trainings were a terrific example of the resources and experience other federal training centers have to offer when holding multidisciplinary educational events.

The ATTC provided financial and logistical support, offered advice on the types of continuing education credits needed by substance abuse treatment professionals, and assisted in obtaining specialized substance abuse continuing education credits. The ATTC also brought their knowledge of the substance abuse treatment system and providers to the table during the planning process, and as a result the trainings were well-tailored to the audience’s needs and background, and were held at times and places that fit well with their schedules.

Ultimately four half-day trainings were held in different regions of Massachusetts in October and November, 2009. These trainings were targeted at professionals responsible for implementing the new policy at substance abuse treatment facilities where they were employed, but were also open to nurses employed at public health departments, hospitals, and clinics. The events were free and online registration was available through http://www.eventbrite.com, a user-friendly website where planners can set up event registration for free if their event is free.

Each training began with a one hour TB 101 presentation by Dr. John Bernardo, (TB Control Officer for MA) followed by an overview of TB in New England in select populations by Dr. Mark Lobato (Medical Officer for the New England Region, CDC Division of TB Elimination). Next, Sue Etkind (Program Manager for the MA TB Division) gave an in-depth presentation on the new policy for Tuberculosis control in substance abuse treatment centers, which was followed by an informational question and answer panel with representatives from the MA Division of TB Prevention and Control and the Massachusetts Bureau of Substance Abuse Services. Dr. Marie Turner, Medical Director for the TB Treatment Unit at Lemuel Shattuck Hospital, wrapped up the training with case presentations from the TB Treatment Inpatient Unit at Lemuel Shattuck Hospital focusing on drug interactions, TB, and substance abuse.

Continuing education credits were a special consideration for these trainings, since the staff working in substance abuse treatment facilities come from a wide variety of professional backgrounds. Besides the traditional credits for doctors and nurses, credits were also available for Licensed Alcohol and Drug Abuse Counselors (LADAC); Certified Alcohol and Drug Counselors (CADC); Marriage, Family, and Child Counselors (MFCC); and social workers.

A total of 216 participants attended the four trainings. The audience was particularly interested in the biological background of TB and medication side effects. Many of the audience members remarked that the training was “much better than expected,” which is high praise from a group mandated to be there!

The Massachusetts Policy for Tuberculosis Control in Substance Abuse Treatment Centers can be viewed at: http://www.mass.gov/Eeohhs2/docs/dph/cdc/tb/alerts_substance_abuse_center_policy.pdf

Submitted by:

Nickolette Patrick, MPH

NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

TB Intensive Workshop – On the Road Again…

Our TB Intensive Workshop was taken on the road again to Fort Wayne, Indiana in October 2009. After the success of the 2008 training in Toledo, OH, we continued close collaboration with the TB Programs in Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and the city of Detroit.

Most of the faculty members and the core content of the two-day course remained the same. Monthly conference calls were key to planning logistics, ensuring shared responsibilities, identifying topics and speakers, and maintaining overall communication. One of the initial planning steps involved reviewing the evaluation results and suggestions for improvements from the previous year.

Special topics in this TB Intensive addressed the role of legal interventions in TB control, TB among immigrants and refugees, improving adherence to TB treatment, and management of medication side effects. Based on feedback from last year’s workshop, a few changes were made:

- A breakout session on “get to know your TB program” was added to provide an opportunity for TB Program staff to meet participants from their jurisdictions, explain their roles and available services, and discuss other relevant issues

- Case studies were added at the end of each day, and featured a panel of speakers who presented several cases for discussion

- Increased efforts were made to reach out to non-traditional providers working in hospital infection control, correctional facilities, college health services, and long term care facilities

- More information on the use of interferon-gamma release assays was incorporated into the lecture about the diagnosis and treatment of latent TB infection

The workshop was held on October 21-22, 2009 at Indiana University - Purdue University Fort Wayne (IPFW). There were 25 participants who attended, including panel physicians from Nepal and Ethiopia. Dr. Lee Reichman, Executive Director of NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute, facilitated the workshop and engaged the participants with questions. Other faculty members also shared their clinical experiences and contributed to the discussions.

Overall, the course was well received with high ratings of the faculty and topics. Participants especially appreciated the interaction offered by the panel discussions and felt that “the case studies were helpful in comprehending the information.” At the completion of the workshop, most participants indicated that they planned to implement specific changes to enhance their TB program. Examples included improving assessment of pediatric TB patients; considering use of a rifampin-based regimen for treatment of LTBI; partnering with local physicians, hospital infection control staff and immigration services; and increasing awareness of TB through staff education and training.

The Office of Academic Affairs at IPFW provided outstanding assistance in terms of training logistics, which allowed us to focus on the course content and enhance the learning experience for the participants. We would also like to acknowledge all of the planning committee members for their contributions, and we look forward to working together on future trainings.

Submitted by:

Anita Khilall, MPH

Training & Consultation Specialist

DJ McCabe, RN, MSN

Trainer & Consultant, Clinical Programs

NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

The Lighter Side

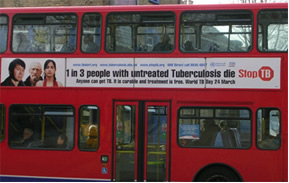

In honor of World TB Day 2010, match the past World TB Day event with the country where it was held.

| Papua New Guinea |

1.  |

| Pakistan |

2.  |

| England |

3.  |

| India |

4.  |

| Tajikistan |

5.  |

| Ghana |

6.  |

back to top

Medical Consultation

Medical Consultation Services: NE RTMCC physicians respond to requests from providers seeking medical consultation through:

- Our toll-free TB Infoline: 1-800-4TB-DOCS and

- Email

During each consultation, the GTBI consultants will advise providers of TB Program resources for consultation in their jurisdiction. In addition, TB programs will be informed of TB cases with public health implications such as MDR/XDR-TB, pediatric TB in children <5, or potential outbreak situations.

More information about our consultation service, including downloadable Core TB Resources, can be accessed at http://globaltb.njms.rutgers.edu/services/medicalconsultation.html Medical Consultant Web-Based Grand Rounds: Periodically, designated TB program medical consultants are invited to participate in a web-based TB case conference (or grand rounds). Consultants are encouraged to present challenging TB cases on which they would like feedback from their colleagues throughout the Region. The next grand rounds will be held this Fall and we will notify TB programs when a date and time have been established. TB program medical consultants who would like to present a case should contact Dr. Alfred Lardizabal at 973-972-8452 or lardizaa@njms.rutgers.edu.

back to top

Upcoming NE RTMCC Training Courses Planned for 2010

Courses are open to participants in the 20 project areas (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, NJ, New York State, New York City, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Washington DC, Detroit, Baltimore, and Philadelphia) which are served by the Northeastern National Tuberculosis Center.

Individuals outside of this region who wish to attend our training courses should first contact their Regional Training and Medical Consultation Center to check if a similar course is being offered. If this is not the case, the out-of-region participant may then register for this course.

Click here for the list of upcoming courses.

back to top

Links - Other TB Resources

Division of Tuberculosis Elimination

The mission of the Division of Tuberculosis Elimination (DTBE) is to promote health and quality of life by preventing, controlling, and eventually eliminating tuberculosis from the United States, and by collaborating with other countries and international partners in controlling tuberculosis worldwide.

TB Education and Training Resources Website

This website is a service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. It is intended for use by TB and other healthcare professionals, patients, and the general public and can be used to locate or share TB education and training materials and to find out about other TB resources.

TB Education & Training Network (TB ETN)

The TB Education and Training Network (TB ETN) was formed to bring TB professionals together to network, share resources, and build education and training skills.

TB-Related News and Journal Items Weekly Update

Provided by the CDC as a public service, subscribers receive:

- A weekly update of TB-related news items

- Citations and abstracts to new scientific TB journal articles

- TB conference announcements

- TB job announcements

- To subscribe to this service, click here

TB Behavioral and Social Science Listserv

Sponsored by the DTBE of the CDC and the CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN), this Listserv provides subscribers the opportunity to exchange information and engage in ongoing discussions about behavioral and social science issues as they relate to tuberculosis prevention and control.

Other RTMCCs

The Curry International Tuberculosis Center serves: Alaska, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, Federated State of Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Republic of Marshall Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Republic of Palau.

The Heartland National Tuberculosis Center serves: Arizona, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin.

The Southeastern National Tuberculosis Center serves: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

back to top

Key Contacts

- Lee B. Reichman, MD, MPH - Executive Director

- Reynard J. McDonald, MD - Medical Director

- Bonita T. Mangura, MD - Director of Research

- Eileen C. Napolitano - Deputy Director

- Nisha Ahamed, MPH, CHES - Program Director, Education and Training

- Nickolette Patrick - Northeastern Spotlight Editor

- Alfred S. Paspe - User Support Specialist/Webmaster

back to top