Dear Colleague:

Dear Colleague:

It was a pleasure to see so many of you in Atlanta this summer at the TB Education and Training Network/TB Program Evaluation Network Conference. As I mentioned in my opening speech at the Conference, one of the most important tools we have in our fight against TB is partnerships, and it continues to be a pleasure partnering with you in education and training activities.

I’d like to briefly emphasize two simple actions to strengthen advocacy that were presented at the TB ETN/TB PEN conference. The first is an advocacy moment: speaking with the press is an opportunity not just to educate the public, but also advocate for TB funding by highlighting how we’re battling an ancient disease we’ve long since known how to prevent and cure. The second is using success stories and images to increase awareness, educate decision makers, and mobilize resources. Frequently TB is in the news only when something goes wrong, and we miss the chance to showcase accomplishments and advances. We welcome submissions to the Northeastern Spotlight about your successes!

In this issue of the Northeastern Spotlight, the Behavioral Research in TB Control feature launches a new series presenting TB control interventions based on behavioral or social science findings, with the first installment discussing the use of peer workers in TB control. We profile Maureen Murphy, TB Control Program Manager for Ohio, and her efforts advocating for comprehensive and client-centered case management programs. We also have articles highlighting our TB Program Managers’ Workshop in distance learning format and CDC’s updated IGRA guidelines. Finally, we also introduce our forthcoming video and discussion guide about delivering rapid HIV test results, which was created in partnership with the Federally Funded Training Centers in New England.

As always, we look forward to seeing you at upcoming trainings and conferences!

Lee B. Reichman, MD, MPH

Executive Director

Northeastern RTMCC and the

Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

Watsonian Society Honors Lee Reichman

Dr. Lee Reichman, Executive Director of the NJMS Global TB Institute, received the Honorary Public Health Advisor (PHA) Award this month at the 23rd Annual Watsonian Society Banquet in Atlanta. For more than 5 decades PHAs have been key partners with CDC and health department scientists and medical epidemiologists in effectively and efficiently implementing, managing, and evaluating cutting-edge public health interventions.

Dr. Lee Reichman, Executive Director of the NJMS Global TB Institute, received the Honorary Public Health Advisor (PHA) Award this month at the 23rd Annual Watsonian Society Banquet in Atlanta. For more than 5 decades PHAs have been key partners with CDC and health department scientists and medical epidemiologists in effectively and efficiently implementing, managing, and evaluating cutting-edge public health interventions.

Throughout his career, Dr. Reichman has worked with and supported PHAs in the New York City Department of Health, the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, the UMDNJ Global TB Institute, and at CDC while serving on various committees, research projects, and grant-related activities. He consistently utilized and supported the activities, leadership abilities and roles of his PHAs. He collaborated with them during consultations and trainings, and recognized their accomplishments in his books (e.g., “Timebomb”). Through all of these achievements and efforts, Dr. Reichman established a well deserved reputation among his PHA colleagues for never missing an opportunity to support and promote the concept of PHAs in his discussions and advocacy with local, state and national policy makers and leaders.

The related photo depicts the former two legendary giants of the New York City TB Program (Dr. Reichman who served as TB Controller in the early 1970s and Dr. Tom Frieden who served as TB Controller in the late 1980s where he notably stemmed the HIV-related TB epidemic there). Dr. Frieden, now the CDC Director, spoke briefly at the banquet and acknowledged Dr. Reichman as a model for public health leadership and advocacy. And both profusely praised the role PHAs have played throughout their careers in ensuring that science-based programs were effectively operationalized and sustained.

Chris Hayden, a former PHA and GTBI employee for many years, sent an email to Watsonian Society members reminding them of Dr. Reichman’s fondness for colorful bowties, and encouraging banquet attendees to honor Dr. Reichman by wearing a bowtie to the festivities. The result was a colorful and well-attired crowd!

back to top

It’s Not About Location: Moving the Live TB Program Managers Workshop to a Distance Format

When they do not come to the course, bring the course to them.

--Anonymous Training Guru

In these tough times, serious cuts have been made to public health programs. One of the most unfortunate cuts has been for travel to training courses and conferences. Here at the RTMCC we have seen this affect our course participation, especially for non-medical and non-nursing courses. Our TB Program Managers’ Workshop has been running for over 10 years, but recently we have been experiencing reduced enrollment— according to our regional partners, staff are less able to travel.

So how does one get trained and network with colleagues when one is not allowed to cross state lines? To answer that question, we explored an interactive distance learning format for our TB Program Managers’ Workshop. The first course of this type occurred in December 2009 and the second in June 2010.

The original 3-day live course had to be changed to something manageable and effective over a distance while covering the same principle content. We had to come to terms with the fact that a distance course needed to be shorter and try to engage people who are not sitting face-to-face. Accomplishing this was not an easy task.

Therefore, we took a hard look at the course agenda and considered what could potentially be eliminated as not being directly related to management skills (such as clinical topics) and what would serve well in a live format versus a recorded format. We ended up cutting 15 hours worth of content down to 9 hours. This new agenda included topics on surveillance and epidemiology, assessment of nurse case management and contact investigation practices, program evaluation, staff training, infection control, laboratory methods, genotyping, and ensuring culturally competent staff. These topics were taught by staff from five different TB jurisdictions and the RTMCC.

We also had to balance how large a block of time trainees could spare and over how many days. Distance learning is accessible - but, as reality would have it, when someone is participating from their office they are more liable to be pulled away for other duties and miss parts of the training. Therefore, we tried a new format consisting of three 2-hour live “webinar-type” sessions with 5 recorded lectures, and online versions of the pre-and post course tests and evaluations. The course also incorporated an interactive exercise on the interpretation and use of surveillance data. One of the features from the live version that we included was the use of a reflective journal to explore how one would incorporate topics from the course into everyday work responsibilities.

Without delving into the typical detailed training statistics of how much knowledge was gained and how faculty and course objectives were rated, it is important to share what participants thought of these first ventures. Participants liked not having to travel for training and that they could complete some of the course portions at their own pace. The sessions on developing training and cultural competency were considered the most practical, and sessions on program evaluation and surveillance data were helpful in bringing seemingly unreachable topics to an understandable and applicable level.

We do need to enhance methods to encourage full group participation, since the web-based format made it challenging to draw out participants who tended not to join in during group discussions. There were also suggestions for other ways to break the course into different types of meeting times; suggestions ranged from increasing the number of live sessions to making the live sessions longer and allowing for breaks. There are many opportunities to apply some lessons from these two offerings for the next course. However, it’s safe to say that distance learning for state and big city program managers and local clinic managers is a sure way to ensure continued competency and sharing of knowledge in the face of travel restrictions.

Submitted by:

Rajita Bhavaraju, MPH, CHES

Training and Consultation Specialist

NJ Medical School Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

The Use of Peer Workers in TB Control

The past four installments of this column have highlighted various studies of the CDC-funded Tuberculosis Epidemiological Studies Consortium which have a behavioral/social science focus; namely, Task Orders 13, 9, 11, and 12. With this installment, we will now begin a series presenting various interventions in TB control that are based on behavioral or social sciences findings. The first of this series concerns peer workers.

Background

Peer workers have been present in a variety of health care settings for centuries. They are an important component of efforts to improve primary health care in the developing world, notably in the scaling up of services and treatment for HIV 1. In recent decades in the US, peers are recognized as having the potential to strengthen patient-centered, culturally-responsive health care at relatively low cost 2, 3. A nation-wide assessment found that in 2000, 86,000 non-professional, community-based workers participated in health promotion, prevention and treatment efforts across the US 2. Peers work under a variety of titles, including “community health workers,” “lay health advisors,” and “promotores,” and are often used in outreach for breast cancer screening, hypertension, HIV prevention, and other diseases or conditions. In general, peers have been used more in prevention and supportive services than in treatment settings.

Defining Peer Work

Peer workers are trained, non-professional health care workers. They share key characteristics with a target population, such as: 1) community membership, gender, race/ethnicity; 2) disease status or risk factors; and/or 3) salient experiences, e.g. drug use, sex work, incarceration.

Peers can play a variety of roles. As part of a Community Advisory Board or other planning body, they can provide input about unmet needs and barriers to services. When serving in outreach or navigation roles, peers can remove barriers so that patients receive needed care. Peers can be valuable members of multidisciplinary teams focused on adherence and treatment completion.

Why Use Peers?

Peers can make a contribution in many ways: being from the local community and having undergone TB or Latent TB Infection (LTBI) treatment, they may have greater credibility with patients. They can serve as effective role models, whose similarity to patients strengthens patients’ confidence that they can achieve goals that peer workers have reached. Their shared experiences may allow peers to form a closer bond with patients than professionals have.

Behavioral/Social Science Theory

Current descriptions of peer worker projects may mention theories used to deliver peer services, such as Prochaska’s Stages of Change, the Information-Motivation-Behavior model, or social diffusion theory 4. Rarely is any attention given to theories about peer work itself. Peer work is usually conceptualized as a form of social support, which has many forms (instrumental, informational, appraisal, emotional) 5. A variety of social cognitive and social comparison theories may also be at play, involving such concepts as self-efficacy (one’s belief in one’s ability to accomplish a certain task, such as taking medicines regularly), belief in and adherence to group norms, and empowerment 6. This is an area for further exploration.

Peer Studies in TB/LTBI

Several studies in developing countries used peers for treatment of TB disease (South Africa7, Philippines8), and the World Health Organization Stop TB Strategy supports the integration of former and current patients into all aspects of TB detection, program development, and services.

The experiences of TB patients help fellow-patients to cope better with their illness and guide National TB Projects in delivering services responsive to patients’ needs. Ensuring that patients and communities alike are informed about TB, enhancing general awareness about the disease and sharing responsibility for TB care can lead to effective patient empowerment and community participation, increasing the demand for health services and bringing care closer to the community. To this end, National TB Projects should provide support to frontline health workers to help them create an empowering environment, for example by facilitating the creation of patient groups, encouraging peer education and support, and linking with other self-help groups in the community.

World Health Organization Stop TB Partnership,

THE STOP TB STRATEGY Building on and enhancing

DOTS to meet the TB-related Millennium Development Goals (p.15)

In the US, peer workers have been used less often in treatment of TB disease; however, they may play a role in the treatment of LTBI (TLTBI). At present, the dominant treatment modalities for TLTBI are self-administered treatment and Directly Observed Therapy for LTBI. DOT for LTBI was found to be effective for populations at very high risk but is too expensive for wider use. Self-administered TLTBI results in poor outcomes: in general clinical populations, at best 50% of LTBI patients complete treatment, and rates are often far lower 9. Thus, support from peer workers presents a treatment option with relatively low costs but which might lead to improved adherence and completion rates.

Four US studies assessed the effectiveness of peers to support adherence to and completion of treatment for LTBI 10-13. Secondary objectives included assisting with TST screening, reaching out to specific populations, and providing health information to targeted populations.

All four studies were randomized clinical trials comparing peers to monetary incentives and usual care (in the Tulsky and Malotte studies, peers were involved in providing DOT for LTBI). The Tulsky and Malotte studies found higher completion in participants who received monetary incentives compared to those who had a peer worker, while the Chaisson and Morisky studies found no differences.

Harlem Peer Studies

The authors were involved in two studies funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) which tested the effectiveness of peers in improving adherence and completion of treatment for LTBI. In the first, Pathways to Completion, two peers who had been treated for TB disease provided informal counseling, service navigation, and support for adherence in bi-weekly meetings with participants assigned to the experimental group (peers did not observe pill-taking). In this randomized clinical trial, statistically significant differences were found in completion rates between experimental and control participants – around 68% of experimental participants completed treatment, compared to 44% of controls. Significant differences were maintained when comparing experimental substance abusers to others, but not when comparing experimental homeless participants to others.

The second NHLBI study was the Treatment Adherence Partnership Alliance Study (TAPAS). Consistent with the patient population at Harlem Hospital, two peers were hired who were African-American, one was Latina, and one was African to serve a West African population. While similar to Pathways, this intervention was more developed and was based on a theoretical model – Weinstein’s Precaution Adoption Process Model -- which is a stage-based model similar to Prochaska’s Stages of Change model but more appropriate to LTBI 4.

Peers in TB Control

An ongoing issue in the overall utilization of peers is the lack of secure funding for this work. The studies using peers in LTBI treatment mentioned above were all funded through research grants and thus did not provide on-going support for the peers who worked on them. At the current time, a TB clinic interested in using peers would need to use general operating funds. A clinic manager might well find that the improvements in appointment-keeping and treatment completion are well worth the relatively small amount invested.

It must be said that scientifically rigorous studies have not shown unequivocal support for the effectiveness of community-based non-professional health care workers. Several authors point out that more rigorous attention to developing and following evidence-based protocols for designing peer programs as well as recruiting, training, and supervising peers are needed in order to increase the effectiveness of peer interventions 14, 15. To our knowledge, one peer training curriculum and one supervisors’ guide dedicated to LTBI treatment support are available to US audiences 16, 17, and a limited number of “best-practice” and peer-reviewed resources oriented to other diseases are available on-line. Those who have worked with peers know of the difference they have made in clients’ lives and of their contribution to adherence and treatment completion. Given this anecdotal evidence, as well as accumulating evidence from other areas of health care delivery, the current challenge is conduct well-designed studies that accurately capture the many contributions of peer workers to TB control.

Resources:

In addition to the citations in this article, further information about peer programs and peer training may be obtained at website of the PEER Center (www.hdwg.org/peercenter). These materials were developed for HIV programs but much will be applicable to TB.

1. Celletti F, Wright A, Palen J, et al. Can the deployment of community health workers for the delivery of HIV services represent an effective and sustainable response to health workforce shortages? Results of a multicountry study. AIDS 2010;24 Suppl 1:S45-57.

2. US DHHS HSRA, Bureau of Health Professions. Community Health Worker National Workforce Study. 2007.

3. US DHHS. Community Health Advisors: models, research and practice, selected annotations - United States. Vol 2. Washington, DC; 1994.

4. Glanz K RB, Lewis FM, ed. Health Behavior and Health Education. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002.

5. Dennis CL. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2003;40:321-32.

6. Turner G, Shepherd J. A method in search of a theory: peer education and health promotion. Health Educ Res 1999;14:235-47.

7. Wilkinson D. High-compliance tuberculosis treatment programme in a rural community. Lancet 1994;343:647-8.

8. Manalo F, Tan F, Sbarbaro JA, Iseman MD. Community-based short-course treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in a developing nation. Initial report of an eight-month, largely intermittent regimen in a population with a high prevalence of drug resistance. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:1301-5.

9. Hirsch-Moverman Y, Daftary A, Franks J, Colson PW. Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: systematic review of studies in the US and Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:1235-54.

10. Morisky DE, Malotte CK, Ebin V, et al. Behavioral interventions for the control of tuberculosis among adolescents. Public Health Rep 2001;116:568-74.

11. Malotte CK, Hollingshead JR, Larro M. Incentives vs outreach workers for latent tuberculosis treatment in drug users. Am J Prev Med 2001;20:103-7.

12. Chaisson RE, Barnes GL, Hackman J, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of interventions to improve adherence to isoniazid therapy to prevent tuberculosis in injection drug users. Am J Med 2001;110:610-5.

13. Tulsky JP, Pilote L, Hahn JA, et al. Adherence to isoniazid prophylaxis in the homeless: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:697-702.

14. Schneider H, Lehmann U. Lay health workers and HIV programmes: implications for health systems. AIDS Care 2010;22 Suppl 1:60-7.

15. O'Brien MJ, Squires AP, Bixby RA, Larson SC. Role development of community health workers: an examination of selection and training processes in the intervention literature. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:S262-9.

16. Charles P Felton National Tuberculosis Center. Peer Support for LTBI Treatment Adherence and Completion: Training Curriculum and Facilitator's Guide; 2006.

17. Charles P Felton National Tuberculosis Center. Peer Support for LTBI Treatment Adherence: a Manual for Program Managers and Supervisors of Peer Workers; 2003

Submitted by:

Paul Colson, PhD, Program Director

and Julie Franks, PhD, Health Educator and Evaluator

Charles P. Felton National TB Center

back to top

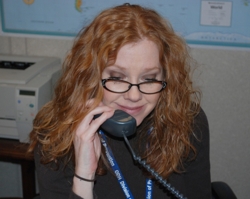

Staff Profile: Maureen Murphy, RN, BSN -- Ohio TB Control Program Manager

Ohio TB Control Program Manager Maureen Murphy has had many entertaining experiences during her tenure as a healthcare provider and public health professional. “When I retire, I want to take my public health stories on the road and do a stand-up comedy routine working the medical conference circuit,” she joked.

Ohio TB Control Program Manager Maureen Murphy has had many entertaining experiences during her tenure as a healthcare provider and public health professional. “When I retire, I want to take my public health stories on the road and do a stand-up comedy routine working the medical conference circuit,” she joked.

Her professional work has certainly provided her with ample material: She began her professional career working as a birthing coach and lactation consultant in rural Ohio, which has a large Mennonite population where women frequently opt for home births. Maureen went to nursing school believing she was going to be a midwife but somehow ended up as a medical staff nurse and then a charge nurse at an urban hospital in Dayton. After three years, Maureen switched gears and joined the Montgomery County STD/HIV Clinic as a client-centered counselor and nurse clinician.

“In my personal life I do a lot of advocacy work and am a staunch feminist, and in the clinic it was difficult to see women coming in again and again who were sex workers or who were in physically and emotionally abusive relationships,” Maureen commented. “We were also contracted to do STD exams for sex offenders, which was very difficult because many of the offenders had molested children. It’s really tough to do this over a long period of time, and I started to get burnt out.”

Maureen switched over to a case manager position at the Montgomery County TB Program, and loved working with TB right from the start. “Having been a nurse in an urban hospital, I was pretty familiar with TB,” Maureen said. “And having been an STD nurse was helpful background experience, since we did have a fair number of TB/HIV co-infections.”

At the time, Montgomery County was not so comprehensive in their case management, and Maureen felt like holistic care and comprehensive case management were an essential part of the process. She made it part of her job to go to the food pantry if a patient was in isolation, help patients fill out paperwork for food stamps, and talk with them about other social services like Medicare and Medicaid. In this way, Maureen helped not just TB patients but also their families, and she found this very rewarding. “The reality of it is I’m a bleeding heart, and I’m an activist!” Maureen stated. Incorporating social services and social support into routine case management also changed the relationship between patients and case workers. Treatment completion was much easier, and undocumented workers became less of a flight risk when they saw that the case manager was there to help them rather than get them into trouble with immigration authorities.

Maureen’s most rewarding case of TB was a woman in her early 40s who worked in a long term care facility. She had been symptomatic and working for six months by the time she was diagnosed with advanced TB disease. When Maureen went to interview the woman at her house, she discovered that the woman had two children living with her at home: a 17 year old son with no arms and a 25 year old daughter with severe cognitive limitations. Had she not been diagnosed with TB, this woman might never have known that her children were eligible for medical benefits, monetary benefits, occupational therapy, and food assistance. There were over 300 contacts in the long term care facility, the converters were successfully identified and 100% completed LTBI treatment. But Maureen considers the real success is that she was able to help this woman and her family receive the help they needed.

Maureen’s most rewarding case of TB was a woman in her early 40s who worked in a long term care facility. She had been symptomatic and working for six months by the time she was diagnosed with advanced TB disease. When Maureen went to interview the woman at her house, she discovered that the woman had two children living with her at home: a 17 year old son with no arms and a 25 year old daughter with severe cognitive limitations. Had she not been diagnosed with TB, this woman might never have known that her children were eligible for medical benefits, monetary benefits, occupational therapy, and food assistance. There were over 300 contacts in the long term care facility, the converters were successfully identified and 100% completed LTBI treatment. But Maureen considers the real success is that she was able to help this woman and her family receive the help they needed.

Like many parts of the country, one of the biggest challenges facing the Ohio TB Program is the decline in TB expertise. “We are seeing a large number of baby boomers retiring in Public Health,” Maureen said. “The average age of a public health nurse in Ohio is over 55. Health departments are being downsized, and there are 10 state-mandated furlough days per year for the public health workforce. Providers contact us because they’ve seldom or never seen a case of TB or LTBI and don’t know how to manage the case. Outside of the urban areas, this has become the norm.” In response, the Ohio TB program is engaged in thoughtful planning about how they will provide excellent care when there’s so much loss of expertise in the public health and clinical workforce.

Some concrete steps the Ohio TB Program is taking to strengthen TB expertise include joining conference calls for medical providers to discuss available TB services, updating the state website to provide more comprehensive information about TB, and spreading the word about free TB consultation services by the state. The program also provides at least five regional trainings each year covering TB basics, in addition to fulfilling requests for specific trainings.

In her spare time, Maureen enjoys spending time with her two grown children and two year old grandson. She enjoys cooking Mexican food, a skill she picked up working in the restaurant of some extended Mexican family members while growing up. She enjoys travelling to new places, and her favorite trip was to Ireland in 2001, where she went for two weeks and ran the Dublin City Marathon.

If all these stories have piqued your interest in Maureen and you can’t wait for her post-retirement comedy routine, she has graciously volunteered to preview some stories if you come chat with her at a conference!

Submitted by:

Nickolette Patrick, MPH

Training and Consultation Specialist

NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

New Product: Delivering HIV Rapid Test Results—Video and Discussion Guide

Last year, the Minority AIDS Initiative released a request for proposals to the Regional Federal Training Center Collaboratives (FTCCs) in order to increase collaborative activities across centers. The Region I (New England) FTCC proposed and was funded to create a video and accompanying discussion and resource guide about delivering HIV rapid test results.

Region I Federal Training Center Collaborative Partners:

- Global Tuberculosis Institute

- Region I Family Planning Training Center

- Sylvie Ratelle STD/HIV Prevention Training Center

- New England AIDS Education Training Center

- New England Addiction Technology Transfer Center

With the increase in rapid and routinized HIV testing, more health care workers are faced with the challenge of giving HIV rapid test results. Many providers in the Region I network expressed anxiety and uncertainty about delivering this news to clients. The recent emphasis placed on offering HIV testing to people with TB could mean that more providers serving TB patients are beginning to offer rapid HIV testing, and would benefit from this new product.

As part of the grant application, a literature review and extensive search found few materials about the specific challenges and concerns when delivering HIV rapid test results. The Region I FTCC partners began creating the product by conducting key informant interviews and talking with their stakeholder networks to get an idea of provider concerns. After the scope and focus of the video was collaboratively agreed upon, a script was written, reviewed, and filmed. “Talking head” segments with real clients and providers were also filmed, and the Region I FTCC partners offered comments on the rough cut of the video.

The resulting product is called Delivering HIV Rapid Test Results: Experiences from the Field . It is a short (approximately 30 minute) video that combines real stories from providers delivering rapid test results and clients learning their test results, as well as scripted vignettes that illustrate key points. It is designed so that it can be used both for individual study as well as in a group learning setting. The goals of the video are to:

- Demonstrate counseling approaches for effectively and compassionately delivering results

- Offer personal experiences and perspectives from a group of diverse clients who have received both positive & negative test results and from providers who have given results

- Emphasize the importance of providing culturally appropriate services and referrals

The 26 page discussion and resource guide includes:

- Annotated scripts for the vignettes and discussion questions for each vignette

- Helpful statements and questions, including sample language providers can use with clients

- Counseling tips for responding to difficult emotions

- Tips from Region I clients who have received HIV test results

- Tips from Region I providers who deliver HIV rapid test results

- What clinic/program administrators can do to support delivery of HIV rapid test results

- Making effective referrals, including a list of information and referral resources

The video and accompanying discussion and resource guide will be available to view online and download beginning at the end of October 2010. Hard copies of the materials (DVD and printed discussion and resource guide) should be available in November. You can access the guide

here.

Submitted by:

Nickolette Patrick, MPH

Training and Consultation Specialist

NJMS Global Tuberculosis Institute

back to top

CDC Updates IGRA Guidelines

In June, the CDC released the much-anticipated update to its 2005 guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test (QFT-G). The new report covers all FDA-approved interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs), including the QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube test (QFT-GIT) and the T-SPOT.TB test (T-Spot).

Updated Guidelines for Using Interferon Gamma Release Assays to Detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection – United States, 2010 was published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) on June 25, 2010. This report guides public health officials, health-care providers, and laboratory workers in their use of FDA-approved IGRAs in the diagnosis of M. tuberculosis infection in adults and children. In brief, tuberculin skins tests (TSTs) and IGRAs (QFT-G, QFT-GIT, and T-Spot) may be used to help diagnose M. tuberculosis infection, to conduct surveillance, and to identify persons likely to benefit from treatment. Additional recommendations address quality control, test selection, and medical management after testing. For example, the guidelines describe:

- Situations in which an IGRA is preferred but a TST is acceptable;

- Situations in which a TST is preferred but an IGRA is acceptable;

- Situations in which either a TST or an IGRA may be used without preference; and

- Situations in which testing with both an IGRA and a TST may be considered.

The authors stress that although studies of IGRAs to date have not revealed major deficiencies involving various populations, additional research that focuses on the value and limitations of IGRA is needed.

Read the MMWR report.

Reprinted with permission from the Curry National TB Center Newsletter, Summer 2010

CITC Newsletter Editor: Kay Wallis, MPH

back to top

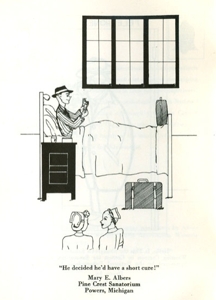

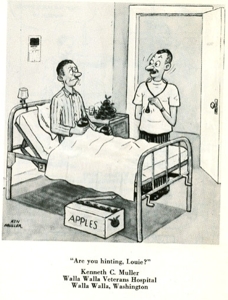

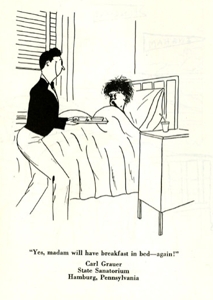

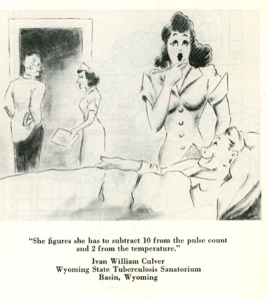

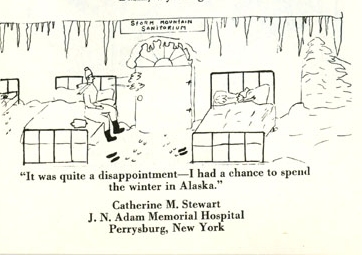

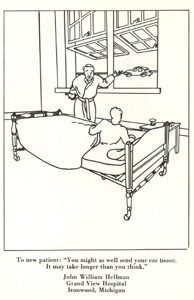

The Lighter Side: Sanatorium Comics

In 1947, the National Tuberculosis Association (which later became the American Lung Association) sponsored a cartoon contest about life in sanatoriums. The contest was open only to TB patients, and the goal was to build morale and help find humor in the sanatorium experience. Submissions were judged by a panel of professional cartoonists, and the winning entries were turned into a booklet called Just for Fun: Cartoons by Patients. Below are some of the winning entries:

*** CLICK IMAGE TO ENLARGE ***

Cartoons from “Just for Fun” published 1947 by the National Tuberculosis Association reprinted with permission © 2010 American Lung Association www.LungUSA.org

back to top

Medical Consultation

Medical Consultation Services: GTBI faculty and staff respond to requests from providers seeking medical consultation through:

- Our toll-free TB Infoline: 1-800-4TB-DOCS and

- Email

During each consultation, the GTBI consultants will advise providers of TB Program resources for consultation in their jurisdiction. In addition, TB programs will be informed of TB cases with public health implications such as MDR/XDR-TB, pediatric TB in children <5, or potential outbreak situations.

More information about our consultation service, including downloadable Core TB Resources, can be accessed at http://globaltb.njms.rutgers.edu/services/medicalconsultation.html

Medical Consultant Web-Based Grand Rounds: Periodically, designated TB program medical consultants are invited to participate in a web-based TB case conference (or grand rounds). Consultants are encouraged to present challenging TB cases on which they would like feedback from their colleagues throughout the Region. The next grand rounds will be held this Fall and we will notify TB programs when a date and time have been established. TB program medical consultants who would like to present a case should contact Dr. Alfred Lardizabal at 973-972-8452 or lardizaa@njms.rutgers.edu.

back to top

Upcoming NE RTMCC Training Courses Planned for 2010

Courses are open to participants in the 20 project areas (Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, NJ, New York State, New York City, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Indiana, Ohio, West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Washington DC, Detroit, Baltimore, and Philadelphia) which are served by the Northeastern Regional Training and Medical Consultation Center.

Individuals outside of this region who wish to attend our training courses should first contact their Regional Training and Medical Consultation Center to check if a similar course is being offered. If this is not the case, the out-of-region participant may then register for this course.

Click here for the list of upcoming courses.

back to top

Links - Other TB Resources

Division of Tuberculosis Elimination

The mission of the Division of Tuberculosis Elimination (DTBE) is to promote health and quality of life by preventing, controlling, and eventually eliminating tuberculosis from the United States, and by collaborating with other countries and international partners in controlling tuberculosis worldwide.

TB Education and Training Resources Website

This website is a service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Tuberculosis Elimination. It is intended for use by TB and other healthcare professionals, patients, and the general public and can be used to locate or share TB education and training materials and to find out about other TB resources.

TB Education & Training Network (TB ETN)

The TB Education and Training Network (TB ETN) was formed to bring TB professionals together to network, share resources, and build education and training skills.

Regional Training and Medical Consultation Centers' TB Training and Education Products

This website provides a searchable list of all 4 RTMCCs' resources.

TB-Related News and Journal Items Weekly Update

Provided by the CDC as a public service, subscribers receive:

- A weekly update of TB-related news items

- Citations and abstracts to new scientific TB journal articles

- TB conference announcements

- TB job announcements

- To subscribe to this service, click here

TB Behavioral and Social Science Listserv

Sponsored by the DTBE of the CDC and the CDC National Prevention Information Network (NPIN), this Listserv provides subscribers the opportunity to exchange information and engage in ongoing discussions about behavioral and social science issues as they relate to tuberculosis prevention and control.

Other RTMCCs

The Curry International Tuberculosis Center serves: Alaska, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming, Federated State of Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Republic of Marshall Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Republic of Palau.

The Heartland National Tuberculosis Center serves: Arizona, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, New Mexico, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin.

The Southeastern National Tuberculosis Center serves: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

back to top

Key Contacts

- Lee B. Reichman, MD, MPH - Executive Director

- Reynard J. McDonald, MD - Medical Director

- Bonita T. Mangura, MD - Director of Research

- Eileen C. Napolitano - Deputy Director

- Nisha Ahamed, MPH, CHES - Program Director, Education and Training

- Nickolette Patrick - Northeastern Spotlight Editor

- Alfred S. Paspe - User Support Specialist/Webmaster

back to top